Meet Bob Meadows, a Shoals original

Perhaps you’ve seen Bob Meadows at Shoals Marine Lab. Tall, kindly, and sporting a most excellent mustache, Bob can regularly be found washing dishes in the kitchen or brandishing his weed whacker out on the trails.

If you’ve ever had the pleasure of conversing with Bob, you’ll know he’s warm, passionate, and selfless. He’s a Shoaler through and through, but what you might not know is that he has a history with SML that predates the lab itself. He’s one of the true Shoals originals.

I recently had the privilege of sitting down with Bob and hearing his story from the beginning. We hope you enjoy this exclusive interview with the amazing Bob Meadows.

C: Thanks so much for talking with me! We thought it would be really cool to tell your Shoals story since you've been a part of it for so long and still come to the island and do awesome things.

Let's start from the beginning. How did you get started with Shoals?

B: I was born and raised in Ithaca, and I went to Cornell as an undergraduate. I think it was during my sophomore year, I took a course with Dr. Kingsbury.

I was born in ‘49, raised in the 60s, and I was a Cousteau kid who wanted to swim with the fishes and become a marine biologist.

Jack (Dr. Kingsbury) was a great teacher, enthusiastic, with a true passion for things. During the course of that course, Jack was working on this other little project he had. He was thinking about building a marine lab on a remote island off the coast of Maine.

He put out a notice for volunteers to help him that summer, summer of 1970, to go out and spend a week on this island that'd been abandoned since World War II to start opening it up again and making it accessible and adaptable to a marine lab.

So, in the summer of ’70, I took a bus up to Portsmouth and hopped aboard the old Viking Star with Captain Jack Arnold. It was pea soup fog, and this was back in the day before GPS and any kind of navigation or radio, really. It was all dead reckoning.

He listened to the foghorn, took a bearing, put an RPM on, and went for about 45 minutes. We stopped out around the islands hearing the bell buoy. He’d take another bearing, go for another 10 minutes, and within a few minutes, Star Island came out of the fog. It was really amazing seamanship to get out to the islands in pea soup fog, and Jack Arnold did all that navigation.

We stayed on Star for the week as there was no access to Appledore. Captain Jack would take us over to Appledore in the old whaler. There were no docks, no nothing, so we’d just land on the rocky shoreline and crawl through the weeds and brush and poison ivy, and we hacked our way to a building, which was Laighton House.

We kind of centered there. We’d have our lunch there, our peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and Kool-Aid or something, and we just kind of went around to the various buildings to try and find trails and roads.

We’d also get physically inside some of the buildings so we could assess them as far as if they were salvageable and what kind of shape they were in. We tried to rediscover all the systems that were on island during the war as far as electrical, water lines, and a well.

Of course, Jack Kingsbury had the vision. We [students] were all kind of just raw energy, not much experience or knowledge.

So that was kind of the beginning of things.

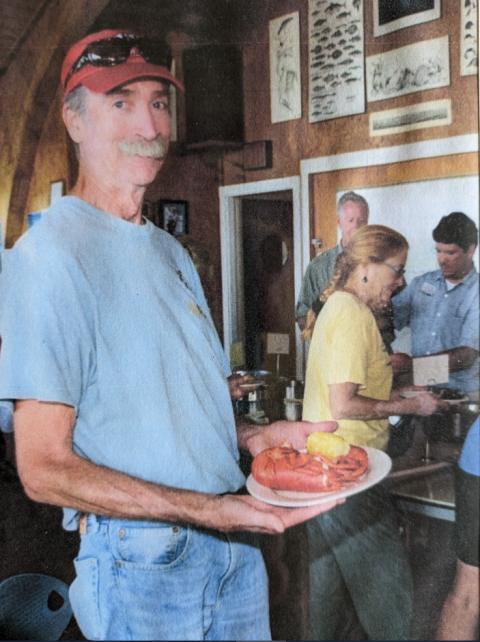

Bob showing off the first & biggest cod caught during a fishing trip off Star Island

C: So, you guys went out there just to figure out what existed. And then you started to actually build things? What happened next?

B: We went out for a week, then [Jack] made another week available to come out. I was going to do that too, but then I injured my knee bicycling, so I couldn't go for the second week.

That winter, Jack got some plans together with the newfound access and knowledge, and actually raised enough money to do certain construction. He physically went around to golf clubs and town halls to give speeches and solicit donors.

He got together to negotiate with Cornell so they would actually allow him to proceed because they were very concerned, they were not fully on board with this whole idea of Shoals as far as liability and where the money’s coming from. That’s normal for a school with big tuition, so it was good on their part. He assured them of the funds, and they actually advanced a limited amount of funding as long as he kept the books in the black.

He hired a contractor who he hoped would be suitable to work on an offshore island and pull the whole thing off.

He selected a man named Dominic from York. Dominic was hired, and then he had to hire a crew, so he solicited at Cornell to hire some student labor.

I applied with a bunch of other people, and I was selected along with a few other friends. We went up that summer of 1971 to start construction and one of the things I can recall is that we built the concrete form for the Grass Lab and started that building.

Releasing Wilson’s warbler at banding station behind the Grass Lab

We discovered this hole in the ground behind the Grass Lab, this big round 2-foot diameter hole with a cast iron ring about 12 feet deep and full of water with a bunch of dead muskrats.

Dominic said, “Okay, find out what’s down there, guys.” We pumped all the water out, got a ladder down there, and shoveled out all this muck and timber. It took more than a day to finally get it cleaned up. Guess what we found at the very bottom of that chamber?

C: What?

B: A pair of ice tongs.

C: Wow.

B: So that was a hotel's ice house. They would harvest [the ice] on Silver (Crystal) Lake and take it down to the ice house. I assume it was right underneath the kitchen where a dumbwaiter would take the ice right up into the kitchen [of the hotel]. The muck was actually sawdust from the timbers because that's how they insulate ice over the summer to have enough for all seasons. That's kind of a neat discovery of some of the history of the island.

C: That's wild. Is that near where the cistern is now?

B: That is the cistern. That little white building, that's the ice house. Shoals is still using it today.

There’s a lot of history on that island out there, so that's one of many stories.

C: How long were you out there doing the construction?

B: We got out there in late May and stayed through about mid-late August until we had to go back to school. I was a sophomore or junior at that time, so I still had one or two more years left to go.

C: You stayed out there the whole summer? Where did you live?

B: That was kind of interesting, too. We were employees of Dominic. There also were people who were employees of Cornell and UNH. Housing was, like, nonexistent out there.

The only place that was really suitable was the Coast Guard house, that's where most people stayed.

But with us being employees of Dominic, we didn't have all the restrictions that the university employees had. My room was actually the second floor from the top in the radar tower with one guy a floor above me and one a floor below. The universities wouldn't allow anybody to live in there, but we did, so we had a penthouse view of the island.

C: Hang on, you mean the radio tower that's on Appledore now? You lived in there?!

B: Yeah, the concrete radio tower.

C: Sounds like such an eventful summer.

B: I graduated from Cornell in the summer of ‘72. I intended to come back out that next summer of ‘72, but unfortunately, I got a job and I had to go and actually make a living. I was hired by Dr. Edward Raney, the ichthyologist at Cornell who was one of the founding members of the lab from the beginning.

I worked on nuclear power plant impact studies down in Delaware Bay, on 316A 316B regulations. Back then, nuclear power plants were a big deal. They were trying to build them everywhere.

I’d come out [to the island] for two weeks every summer from 1972 to 1980. I’d come for two weeks during my vacation and volunteer, but then after 1980, I didn't come back for about 25 years. I think it was 2005 or so when Jack Kingsbury organized a pioneer weekend for all the old-timers to come back and reunite. I had a family and a career then; I just hadn’t had the time to go out and be with the lab too much.

In the last 10 years or so, I've been trying to come out every summer and do some more, to pick things up where I left off.

C: That's amazing, you have such a long Shoals legacy. Did you ever take a class out there?

No, not really. I applied once and I didn't quite make the cut, it was pretty competitive. I wasn't really very academic, I enjoyed more hands-on type of stuff.

I was a field biologist all my life. My primary attire was boots and a rain slicker.

It was probably more important [for me] to know how to repair an engine than it was to know how to dissect squid or something. I never did take a course out there, but I always sat in on things and helped out and observed.

It's a good way to collaborate and network, it was a very valuable experience, as was just knowing Jack.

I was born and raised in Ithaca, so I'd always go back there every summer. I’d always stop in and see Jack in his office in Plant Science and sit down. He’d recap what happened the past year [at Shoals] and tell some of the funny stories about building permits or building inspectors or saltwater or septic systems.

I kept in touch through the years and kind of felt like I was there at Shoals when I stopped by Jack’s and Louise's house.

I got to know Jack increasingly well over the years, and in the last few years, I made a concerted effort to spend more time with Jack because he was a big important mentor in my life.

He showed me how things got done and taught me that you never take no for an answer. If you've got a just and worthy cause, there's always a good way around it, a way to get your work done.

Jack & Louise on the front porch of their house in Norwich, Vermont home during a visit in 2022

C: That's a good motto to live by.

B: I'd try to help Jack and Louise out quite a bit. I’d go up there and stay with them for a few days. I took them down to Bullard Farm in Massachusetts for picnics and stuff.

I’d also spend some time down at their cottage on Cape Cod on Scraggy Neck.

I was there late last year for about a week and a half to help them cook and get around. We’d go shopping for them. It was all to pay them back a little bit for all they gave me.

C: That's so great of you.

B: Me and Jack, we’d just sit in his living room or the back porch in Scraggy Neck and just talk for hours. He talked about his family and his father, his uncles, and those experiences growing up when he first went to college at Massachusetts Agricultural College before it was called Amherst. Then he went to Harvard and Cornell.

It was really great to hear his family's history and his background, and we’d just talk for hours. Though he was at an older age, he was vibrant and engaged. I enjoyed that and I think it was helpful for him and Louise.

Family photo of Jack as a young boy (on the right in the woman’s lap) at their cottage on Cape Cod (Scaggy Neck)

C: With Kingsbury's passing, there's been an outpouring of people sharing their stories and memories of him. It sounds like your relationship with him was pretty special.

You probably know more than anyone what makes Shoals such a unique place and how it furthers people's careers and changes their lives. How was this the case with you? And how did it help get you to where you are today and further your career?

B: It's multifaceted, there are so many aspects. First off, Shoals is just a very unique setting. I mean, its remoteness and its isolation are really big assets. There are so many distractions in people's lives on the mainland, in their towns or cities or colleges.

It's hard to focus sometimes, hard not to get distracted and sidelined by other things. Out there, boy, it just all falls away. You’re right down to core functions there, the environment, the shore. We weren’t so distracted.

It was really great financially, too. There's no way to spend money out there. You didn't really earn much, but you didn't spend anything either, so you could save money and not worry about cars and traveling and gasoline and all those kinds of earthly concerns.

You're also in this community of amazing people, and if you're there all summer, you get this new community every couple of weeks with new experts coming through, too. The student body itself is inspiring. A lot of students have wide-ranging backgrounds and expertise and insights which can challenge your thinking and give you new contacts to pursue. That was great.

I won't say it was a religious experience, but some solitude can be nice at times. You kind of just reflect and review what you're doing and look at your own life. How can I contribute to the island? What can I take with me when I leave?

Again, Jack was one of the biggest mentors in my life and really gave me a good jumpstart on my career and how I handled myself and different ways of thinking and ways of dealing with people

He had a certain level of civility and community in an environment where the way you talk to and deal with people really matters. Not everybody has the ability [he had] and it really allows you to get close to people and let them share their experiences.

When I went out to Delaware with Dr. Raney, I was working with commercial fishermen in Delaware Bay: blue crab fishermen, gill netters, trappers.

I ended up in a kitchen area with them and just talked with them about their trapping experiences, their landings, their takes. I was able to connect with them pretty well. I was this young college kid from upstate New York who didn't talk to outsiders much. But those things I learned up at Cornell and Shoals gave me a good insight and a good rapport with these people. I was a really withdrawn, shy kid growing up and in college, and not very social, but I came out of my shell year by year.

Holding an Atlantic sturgeon young of the year while sampling on the Delaware River south of Philadelphia

C: You were talking to these people while you're trying to do science surrounding their everyday lives while getting them to hopefully trust you.

B: Yeah, you have to translate the vernacular and scientific language and all those technical terms and just get down to the raw sense of common language.

C: Your story is really special and fascinating, and I'm so glad that we'll be able to tell our community more about you. I feel like out on the island, people see you around but maybe don't know who you are. Thanks so much for sharing your story, this was really fun.

B: Hopefully my story can inspire other people by showing what's possible or what can be done. I hope something good comes from that, not just me talking about myself all the time!

C: I think it's great for all people to share their career stories and their experiences, finding their way in life, and doing cool things. I mean, everyone can always learn something from somebody else. I love the transfer of life stories.

B: They call it oral history.

C: Exactly!

We hope you enjoyed this insight into Bob’s long history with Shoals!

If you or someone you know would like to tell their Shoals story, please reach out to the SML staff at shoals.lab@unh.edu.